Different media allows different experiences. Books let your imagination work. Movies integrate dialogue, visuals, music, and editing. Audio has a unique intimacy.

Games, too, allow unique experiences.

While I could talk more about some more specifics–like how games are a highly interactive form of media–I mainly want to focus on two games that have been on my mind lately with the COVID-19 pandemic, a recent pixel art game called Wash Your Hands (2020) and the classic cooperative board game Pandemic (2008).

Both address a similar issue, outbreak, in starkly different ways, showcasing the breadth of games as media. But at the same time, I think they also have a lot in common, namely the ability to clarify abstractions in novel ways.

Pandemic: Modelling Outbreak

Pandemic (2008) is a relatively known board game designed by Matt Leacock, designer of Forbidden Island and Forbidden Desert, where 2-4 players work together to combat and eventually eradicate a series of diseases across the planet.

The gameplay fundamentals are simple. On each turn, the player uses four actions to navigate the board, fight disease, and find a cure. Then, at the end of the turn, they draw two “player cards” that grant new actions but also contain “epidemic” cards that intensify the disease. After the player cards, they draw a set of “infection cards” based on the infection rate and place more disease tokens on the board to simulate the spread of the overall infection. The players must defeat the diseases by finding all four cures before the pandemic spreads too much, leading to their defeat.

Pandemic is a “simulation” game, a game that takes something from real life and models it by using rules and game components. Players then interact with that model, creating different outcomes based on their decisions. In a game about pandemics, this modelling has some thought-provoking parallels.

For one, the explosive spread of certain outbreaks bares a spooky resemblance to reality, along with the relentless growth of the diseases. As players tend one part of the map, another part may quickly get out of hand. Much like real life, the more a city or network of cities is infected, the more quickly the virus grows. Just as we are being told to stay inside to slow exposures and reduce simultaneous cases, “flattening the curve,” players need to constantly monitor and combat cases, keeping them from hitting a critical mass that overwhelms the system.

Next, the “epidemic cards,” which lead to sudden, unexpected growth, mirror the chance events that hurt real-world containment efforts. For example, South Korea’s effort to crack down on the spread early on were challenged by religious clusters and the asymptomatic carrier patient 31 and constructing models has been a challenge for epidemiologists. Pandemic builds uncertainty in its system, just as people and viruses are uncertain.

Last, the different specialists that players play as, ranging from a scientist who can more easily research a cure to the quarantine expert who reduces the spread of new cases, highlight the need for different expertise and cooperation. Players are more effective when pooling their skills and responding to new situations as a team. This fits our current situation: people are more effective working together and pooling resources and abilities–though this isn’t always how things are working out.

However, like any simulation, Pandemic is not perfect. In the card-driven spread of the virus, the disease spreads to whatever site you pull from the deck, regardless of nearby contagion. But, more importantly, the game sidesteps casualties: the human fallout of failure. This leads me to Wash Your Hands.

Wash Your Hands: Cultivating Reflection and Empathy

As Katherine Isbister argues in How Games Move Us, games, like any media, have a unique ability to affect us emotionally. Sometimes this can be quite blunt. For example, Isbister discusses Brenda Romero’s game Train, in which players must fit people, symbolized by yellow pegs, on a train, the goal being to fit as many as possible. After a period of time, the train’s destination gets revealed: Auschwitz. Romero said her goal was for players to feel “complicit,” and players often get a deep sense of guilt and regret.

As a less direct emotional experience, Isbister also cites “flow,” when one gets so engrossed in an activity that they leave self-preoccupation behind. Many games accomplish this, but the game Journey was specifically designed to accomplish this, with its yawning, moving landscape, ambient sound design, and constant movement toward a distant goal.

Wash Your Hands (2020), by Dean Moynihan’s one-man Awkward Games Studio, seems to do both: delivering an emotional punch through quiet design choices.

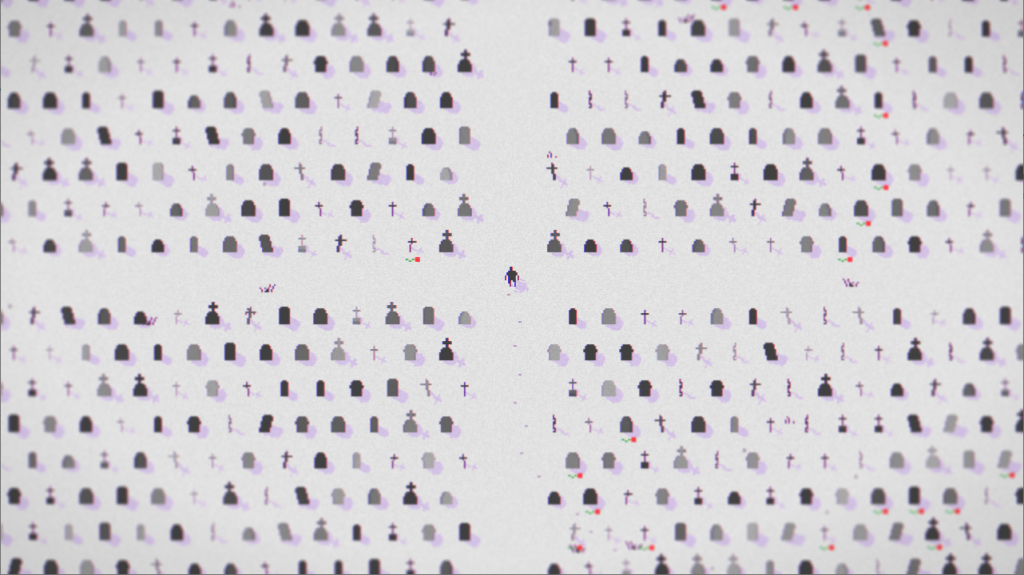

In Wash your Hands, you control an avatar walking in a cemetery, leaving flowers. The catch is that each grave signifies a COVID-19 death, updated as the death statistics update.

Unlike Pandemic, the gameplay is extremely simple, aligning it more closely to a “walking simulator” than a traditional game. It’s all the little things that add to the experience.

First the graphics, simple and understated with largely muted colors. The simplicity contrasts with the action-hero aesthetic of Pandemic, letting the number of graves, neatly organized in prim rows, speak for itself.

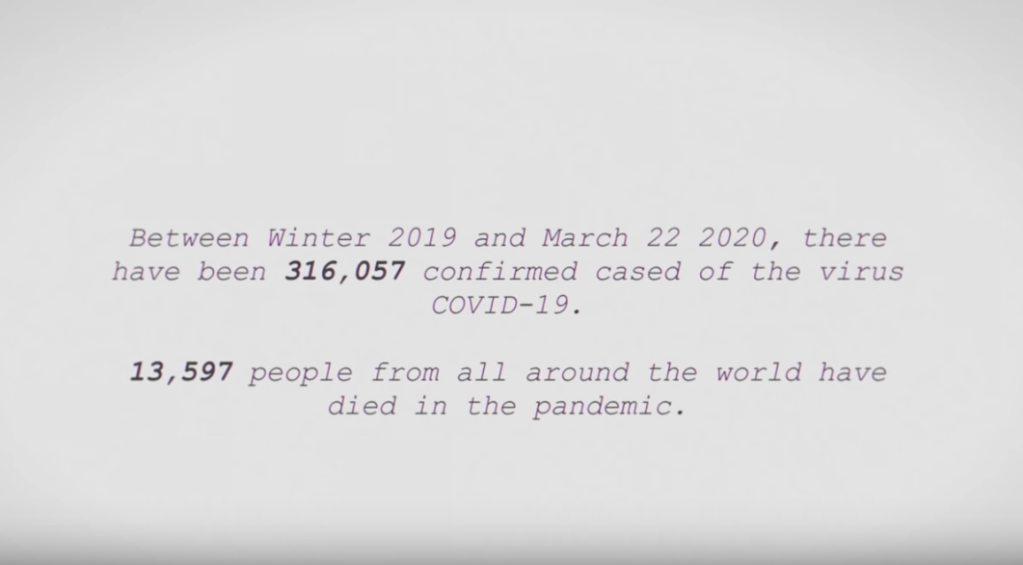

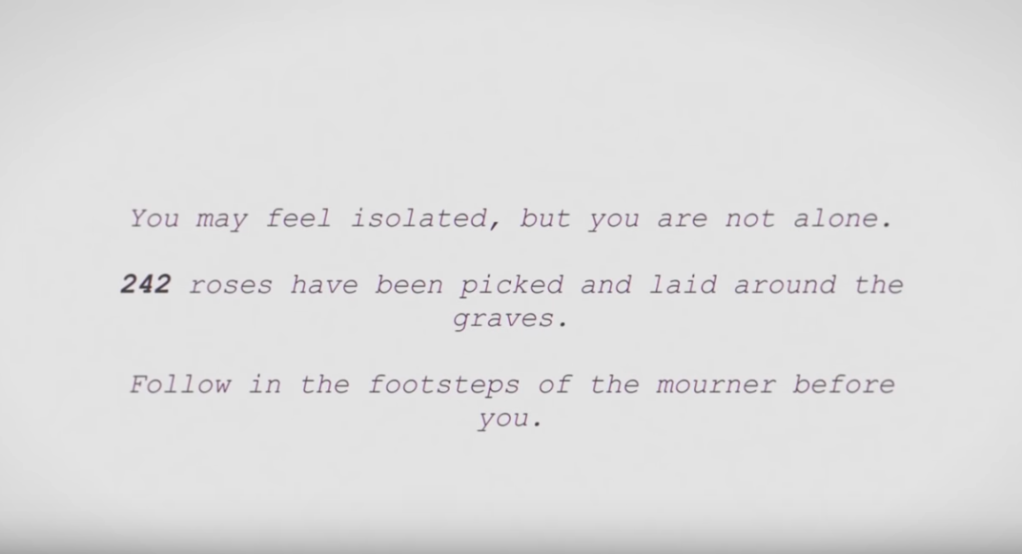

Next, you have the opening screens:

The opening immediately instills a hush with the tally of confirmed cases and deaths, followed by the number of roses left by players and the comforting yet haunting words: “You may feel isolated, but you are not alone. . . . Follow in the footsteps of the mourner before you.”

From this hush, the ambient noise of a forest accompanied by a simple acoustic guitar accompanies the transition to the main game: your avatar in a cemetery surrounded by trees. Then, one simply walks.

Your footsteps leave ghostly traces with a soft crunch of snow audible with each step. Here, the pacing is important, especially when accompanied by the footfall sound. It is slow and meditative.

You then start to come across roses, strewn in the snow. You pluck them up and place them in front of graves with a simple gesture.

But mostly, you are walking, listening to the music, watching the grids of white space and headstone pass by, knowing that each one signifies a human life lost to the disease.

Conclusion: The Power of Clarity

Both Pandemic and Wash Your Hands center on the spread of disease, but they take up their subject matter in completely different ways. But both, in a sense, are teaching tools, or at the very least, tools of clarification.

Amid this tragic pandemic, I have been coming back to issues of clarity–of making sense of things. Because, it’s difficult. The numbers are staggering and relentless. The variables are incalculable. The timeline is shifting and daunting. Not to mention all the information, misleading or accurate.

But amid this uncertainty, I come back to the ability to communicate important truths. Some of these communications are simple and pragmatic, like the famous “flatten the curve” images, Cuomo’s PowerPoint slides, or Dr. Fauci’s clear-spoken advice and predictions. Other communications are reflective and poignant, like The New York Times‘ photo essay on “The Great Empty” and Wash Your Hands.

Amid the noise, tragedy, and acrimony, the power of clarity amid crisis proves more important, as well as the ethical, thoughtful communicators who persist, despite challenges.

I don’t think these games are as important as most of the rhetoric out there regarding this pandemic–though, I think Wash Your Hands is a potent message and experience–but I hope that they help us reflect on the important role that media, of all types, have when shaping our world.

[Title Image: “Rockingham City Shopping Centre empty shelves caused by the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic” by Calistemon via Creative Commons]

![Concept art from This War of Mine [Image courtesy of craveonline]](https://backyardphilosophy01.files.wordpress.com/2015/03/this_war_of_mine_feature.jpg?w=660)